If you don't feel safe, you cannot negotiate Guest: Raheena Lalani Dahya

In this episode of WeCanFindAWay, I sit down with Raheena Lalani Dahya — a mediator based in Canada, and co-author of a recent article on trauma-informed mediation practice. Raheena has been exploring what it means to bring a trauma-informed lens to civil mediation, and why this conversation is becoming increasingly important in the dispute resolution field.

We discuss why mediators are now talking about trauma and how understanding trauma can deepen our insight into human behavior in conflict. Raheena explains how trauma is connected to fear responses and dysregulation, what happens in the brain when people feel unsafe, and how this impacts their capacity to participate fully in mediation.

She introduces key concepts such as the “window of tolerance,” “safety in numbers,” “tend and befriend,” and “name it to tame it,” illustrating how these ideas can help mediators recognize when participants are overwhelmed and create conditions that restore calm and safety. She also discusses this as an ethics issue.

We also talk about the value of drawing from other disciplines — especially neuroscience and psychology — to enrich mediation practice. Whether you’re a mediator, lawyer, conflict resolution professional, or simply curious about how people respond to stress and conflict, this episode offers practical insights into how a trauma-informed approach can help people truly find a way forward.

IE: Hello and welcome back to another episode of We Can Find a Way. My name is Idil Elveris. This podcast is about conflict and alternative resolution methods to resolve it and I try to cover all sorts of conflict in this podcast for practitioners and people interested in dispute resolution with examples from all over the world.

This podcast is sponsored by Dr. Paolo Michele Patocchi, Attorney at Law and Arbitrator. I'm grateful for his engagement with alternative dispute resolution in Turkey by participating in multiple conferences, teaching at Bilkent University in Ankara and now supporting my podcast We Can Find a Way.

In this episode, I spoke with a lawyer and mediator from Canada. Our interview took place in fact when she was in Andorra, so a truly global We Can Find a Way soul, if I may call her like that. Her name is Raheena Lalani Dahya. Recently, she published an article with her co-authors about trauma informed mediation practice. I covered the subject before in We Can Find a Way, but that was from a restorative justice perspective. So this time, I wanted to talk to her about why we are discussing trauma in mediations and, in civil mediation even, and what prompted her to address the needs of vulnerable communities, how trauma affects people's capacity, especially on long tracted conflicts to resolve them. We also discuss how mediators can benefit from other disciplines such as neuroscience. I will give her short bio at the end of this episode, but now let's start with the interview that took place on 20th October 2025.

Thanks for agreeing to talk to me Raheena. Please tell us how did it come about that we are discussing trauma in mediations? Why now? What made the topic the “hot topic” of today?

RLD: Thank you for having me. It's a pleasure to be here.

I think what has happened here is people are understanding that conflicts are dynamic and that the way that people engage with one another is informed by various different contexts and how we behave when we are upset in trauma terms; whether we're able to self regulate or whether we dysregulate during conflict really plays an important part in how we understand conflicts that we partake in and when we're reflecting on them and saying “oh, why did I behave that way? How come this other person who I usually experience is very reasonable, behaved that way?” Alternatively, when we're the third party, so the mediator, trying to understand what's happening in this dynamic. And trauma models give us a wonderful way of seeing different behaviors from a lens that's scientific, that's based on neurobiology. And so I think as people are learning more about psychology and neuroscience, they're leaning into understanding these behavioral changes. I also think the advances in neuroscience that have come through, have given us new language. I think there was a time where people felt that these were very “soft sciences or soft skills”. Whereas now, it's being seen that a lot of this is rooted in neurobiological function. Ideas as ancient as certain yogic ideas are now being demonstrated physically through FMRI imaging. So it's become a “hot topic” because it's found the tipping points been hit, and people understand that the same curiosities we've always had, there's some sources of information and those sources of information that can give us clues. Some of that goes to neuroscience, and within neuroscience are trauma models.

IE: So tell me a little bit more about these trauma models and the language that you have just mentioned in neuroscience.

RLD: There are several trauma models out there. I think one that really helps people understand our own as well as others behaviors is Daniel Siegel 's Window of Tolerance. If you imagine a square and a parabola going through the square, so a line drawn from the bottom; underneath the square; through the square; over the top; and back down again. When we are inside that square, that's when we're connected to something called our prefrontal cortex. Let's just do a little bit of neuroanatomy here.

Our brain is made up of several different parts, and those parts have different functions. Whenever we receive any stimulus whatsoever, it could be me pinching myself. So that's a felt sensation. Or hearing something, so an audio stimulation. Or seeing a beautiful flower, that's visual stimulation. All of that goes in through our brainstem. So it starts in our spinal cord. We get some stimulus. Our spinal cord sends that information through our brain. Now it will go through the back of our brain first. Around our brain stem, and then through our limbic system, which is often referred to as part of the reptilian brain. So that part of our brain governs fight, flight, freeze, and flop. So those are four of the fear responses that exist.

A lot of people know fight or flight. Freeze is exactly what it sounds like. It's, “oh, deer cotton headlights”. Flop is freeze's twin, almost. It's instead of deer cotton headlights, it's where you know, sometimes an animal will seem dead; so that the lion will move on and then later it will get up. So flop is kind of that freeze response, but in a “play dead” response. Next, that stimulus will move through our mammalian brain where a number of our social behaviors come from. It's where our impetus to look after the young. It's why we like puppies and kittens. They have big eyes and little noses just like human babies. And you'll see mammals taking care of interspecie mammals. So there's a lot of pro social behavior that occurs in the mammalian brain. Now I hypothesized, and I actually just ran this by Daniel Siegel himself, that are two other fear responses commonly known as “tend and befriend” or what my co authors and I have referred to as “flock” and the other one known as “fawn” which is a submission compliance response. These live in the mammalian brain. This is our suspicion.

Why do we think there's a difference? Because these require social behaviors. Tend and befriend looks like if a saber toothed tiger is running after you and me, on a savannah a million years ago, we might pick up a couple of babies and run. That's us tending, we're looking to our young and our vulnerable. Or I might pick up a baby and you might support an elderly person or injured person. We're tending in fear. The other thing we do is befriend. And here this could be you and I looking at each other and going: “Oh, there's a threat. Let's join each other in numbers. Because there's safety in numbers”.

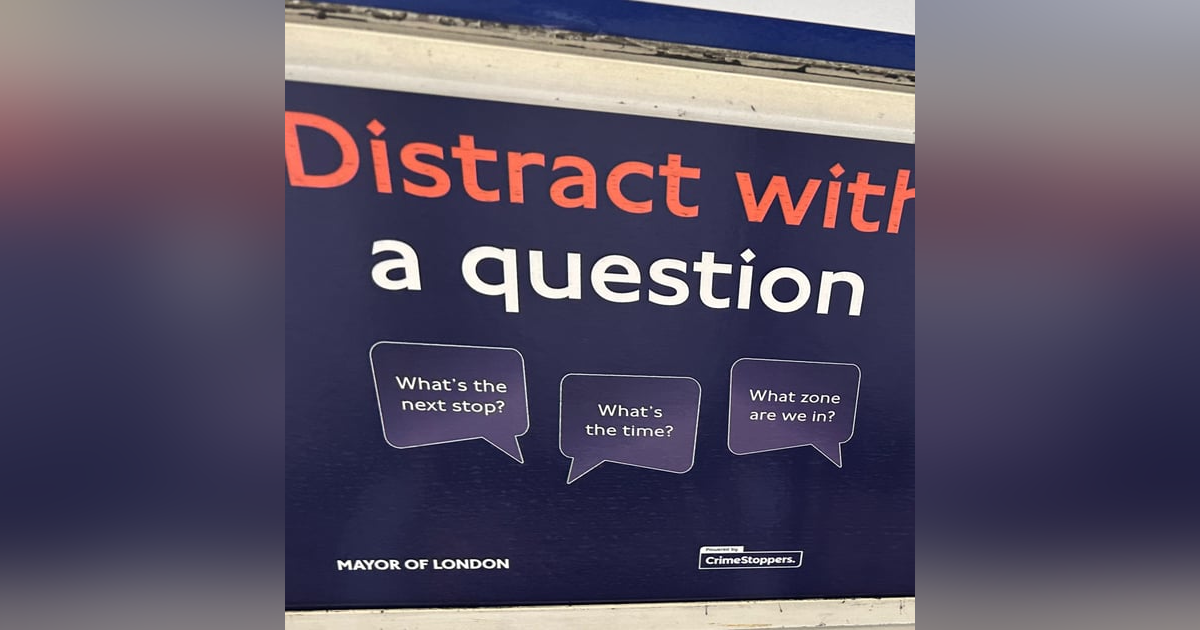

IE: It's really interesting you actually find these tactics in the subway here in London to fight sexual harassment. And the mayor is hanging them. “Oh, pretend like a friend. If you see someone being harassed or racially abused”. So actually they're not only in the field of mediation, but it's also publicly. They're not named like that, obviously.

RLD: Yes.

IE: But they are used as tactics in anti harassment groups, you know, bystander type of trainings.

RLD: Well, that's right. Because at the end of the day, these tactics that are shared are dispute resolution interventions.

IE: Yes, exactly.

RLD: Not named as such.

IE: Right.

RLD: You can see here's advice put forward by, I think you said the mayor of London.

IE: Yes, yes.

RLD: Saying “use a tend and befriend” response.

IE: Right. Or only if you feel safe. And then there's this addition.

RLD: Only if you feel safe, of course. And so one of the things that I find fascinating and that I focus some of my research on is looking at fear responses. In conflict, and then learning what to do about that as a mediator, as someone who's hosting conflict conversations. So to go back to that language question you had, I get a stimulus, let's say I get pinched on the arm, that makes it through my to my brain stem, through my limbic brain, through my mammalian brain, all the way up to my prefrontal cortex. Now, my prefrontal cortex is where we do our thinking, our mathematics, our philosophizing, our rationalization.

When we are connected to our prefrontal cortex, we are in what we call our “window of tolerance”. We are not always connected to our window of tolerance.

IE: It stays in the back. Mammalian brain, taking over.

RLD: Mammalian brain, reptilian brain. So what's happening here? Well, at a minimum, it takes approximately 10 seconds for stimulus to get from the brainstem all the way to the prefrontal cortex.

IE: That's a long time. Anything can happen.

RLD: It's a long time in 10 seconds. And evolutionarily, that's very smart. In 10 seconds, the lion can attack us. We don't want to have to wait 10 seconds to get a thinking brain. And also we don't want to miscalculate how to stay alive. Trying to debate with the lion is probably not going to get us very far, but a fight or flight or freeze or flop response is very much more likely going to safeguard us. Also, in a world of social media, we spend, on average, three seconds per post, which means that we don't have a chance to actually be prefrontally connected while we're scrolling on social media. And this actually gives rise to a different concept that I think about all the time that I've named the “politics and commerce of dysregulation”. So now we know, it takes about 10 seconds to get from our brainstem to our prefrontal cortex. That's a long time, as we both noted, especially when we know the person, especially when we've got a long relationship with them.

Anybody listening to this, close your eyes and think about someone you love who also irritates you. Now, I want you just to imagine that look. I don't need to say more. You know which look you're thinking about, you're more likely to react to that look in less than 10 seconds. So it's in these ways, these sort of behaviors inform how we behave in conflict. And so what I'm interested in is: OK, I can accept that these things come up in conflict. What's happening? Well, when we're within our window of tolerance, so that's within that square, we're connected to our prefrontal cortex. That means we can think, we can rationalize, we can philosophize. We can make well thought through decisions in the stereotypical sense.

Often, either during a conflicted event or a conflict conversation, we're not within our window of tolerance. Where do we go? Where do we dysregulate? We dysregulate in two ways: We can go above, we can exceed our window. That square into something called hyper dysregulation. That can look like crying, screaming, yelling. It can look like shaking or red face. It can look like complete calm on the outside and seething on the inside. Think road rage. Or we can descend below that box into something called hypo dysregulation. This can look like slumped shoulders, flat affect or still face. It can look like dropping, like someone's stomach, they just drop forward. It can feel like…

IE: Getting small.

RLD: Yeah, small. It can look like someone says something and “bam”. You have fuzzy brain. Have you ever tried to do something really complex that you didn't understand and suddenly your brain just feels fuzzy or suddenly you're tired? It can also feel like the onset of cold. Out of nowhere, you're cold. What's happening here is freeze and flop. Live at hypo dysregulation. Our system says “this is unsafe”. So it's not a good choice to go to our prefrontal cortex. Let's freeze or flop. When we hyper dysregulate, we go to fight and flight. These are very logical, rational behaviors seen from a perspective of when we don't feel psychologically safe. And often, by the time someone comes to a mediator, the conflict has escalated so much that they don't feel psychologically safe with the other party or parties and so they need that other person to come in.

It puts an onus on the mediator to have good strong self regulation practices and to know thyself so that we stay within our window of tolerance. And when we're within our window of tolerance, then we're able to make logical, thoughtful process choices for people who are feeling psychologically unsafe. And one of the things we can do with these clients is called co-regulation. This is where we use some of our wonderful mediation skills and tactics to engage with someone who has exceeded their window of tolerance and co-regulate them back into their window. And we have different strategies for this.

You know, many mediators have heard “name it, tame it”. Name the emotion. What's happening here? Well, humans feel safety in numbers. Remember that “tend and befriend” thing I told you about? Say someone says: “Whenever the subject matter comes up, they're always so mean to me. They always make me feel bullied and like I don't belong”. The mediator doesn't have to agree with that. The mediator can remain neutral, but the mediator can say: “that sounds really isolating”. And if that's the right emotion, the party will say something along the lines of: “Yeah, it is. It's super isolating”. And if we get it wrong, and these are experiments, these are little microsocial linguistic experiments: “that sounds like it could feel really isolating”. The answer might be: “No, it's not isolating. It's infuriating”. And then my response is: “Sorry, I got that wrong. It's infuriating”.

What happens is when you name someone's emotion and it clicks, they start to calm down. Why? Because someone's tending to them. They're not alone. There's safety in numbers. And so they can come back into their window of tolerance. Now, when I started researching on this, I could find plenty of material about hyper dysregulation. You'd see it in the negotiation literature, working with the “explosive employee”. All of these are fight and flight responses.

One thing I struggled was there was almost nothing about hypo-dysregulation responses. And yet I could see it in my office. I could see someone who was vehemently in favor of a particular outcome, and then at a certain point in the conflict, shoulders slumped, voice changes, just talk more slowly, almost more lethargically and saying: “You know, it's fine, they can have it”. That, to me, is a very strong indicator that I've got someone in hypo dysregulation. And now they're making a “choice” from a place of lack of psychological safety. And when people walk away from a mediation having come to some agreement and then later say they had buyer's remorse or they felt bullied, often what happened was, using their words, they agreed to something when they weren't within their window of tolerance. It's an ethics issue, and it is unethical for mediators to allow parties to be in a joint session when they're dysregulated because they can come to agreements when they're not psychologically safe. If you look at Hoffman's Ethics, one of them is safety. And if you look at trauma informed principles, one of them is safety. And so the appropriate thing to do is use caucus, take the parties into separate rooms, co-regulate with them if they can't, pause the mediation and reschedule for another day. And I will caution one thing, and I ran into this in my own practice. Sometimes, how we perceive body language is impacted by where we learned our culture and our linguistic culture.

My co-mediator and I were completely stumped because someone was so clear with us they wanted to give an apology and the other party was so clear with us that they wanted to receive the apology. And every time we bought the parties into the same room for this apology, body language wise, from our very Western view, it looked disingenuous. We stopped and got really curious. What we learned was the person who was giving an apology was a woman who was a hijabi and who was older than the opposing party, who was a man who was at least a generation or two younger than her. And it was not proper in her culture to make eye contact during an apology or at all in these particular circumstances. And so what looked like inappropriate body language to us was really us having a Western bias. And then once we figured out what was going on, we had a really cool creative outcome where I had said to the parties, and that woman had had other women from her family of other generations in the room, and they were all from the same family, and I just said: “is it appropriate for a woman of her age and stature to be making eye contact during an apology to this gentleman?” And everybody, including the gentleman, they all said in unison, “no”. So we brainstormed a little and then I said: “well, my co mainator is a man, I'm a woman. Would it work if she were to make eye contact with me and make the apology in front of the gentleman with him knowing the apology is for him?” And everyone said: “yeah, that would work”. And that is how the apology went.

IE: Yeah. It's also. It could be a disability issue. Some people are less tolerant of raising voices because they have autism, ADHD, et cetera. Like, even if you get a little bit excited and start speaking, you know, louder, even though you don't mean anything threatening, it can be perceived like that.

RLD: Yes.

IE: There's just like so many issues there.

RLD: Contextual pieces.

IE: Exactly. Can you please tell us a little bit more about your course that you're teaching at the Polytechnic? What prompted you to address the needs of vulnerable communities?

RLD: So I've always worked in vulnerable party issues, initially in law. So I wrote a dissertation during my bachelors of European International Law, looking at the crime of rape in England and Wales, as compared to the crime of sexual assault in Canada. And so I was already dealing with very vulnerable subject matter. And then that translated into practice working with vulnerable persons. So, my very first cases were taking survivors of domestic violence cases, usually within 72 hours of an attack, often people living on the poverty line. And then I've taken on plenty of other vulnerable persons’ cases as I've gone along through life, and that has included in my mediation practice.

I do think that we all have vulnerabilities and we all have privileges. And it's important to understand our context, understand where we're vulnerable, understand where we have privilege for several reasons. One, is to get a sense of our social location. Two, is to understand where we might be in our window of tolerance based on what we're learning from other people or our own social interactions or professional interactions. Also as mediators, and when I'm training future mediators, which is what I'm doing at Humber Polytechnic, what's really important is for the students and all mediators to understand that you don't have to have the same vulnerability or the same privilege as a party to understand what it feels like to have a privilege and to understand what it feels like to have a vulnerability.

So I'm a woman of color. Being a woman and being of color can be vulnerabilities. I also have significant privileges. I'm bilingual. I see that as a privilege. I'm a lawyer by background. I see my education as a privilege. So in this way, I don't have to say, have the privilege of a doctor to know what it feels like to feel into my own privilege and have some empathy for someone with privilege. I also don't need to have the vulnerability of someone who's had an amputation to know that I have my own feelings of vulnerability. So I may never understand what it feels like to be an amputee, but I do know what it feels like to feel vulnerable. So when I'm being empathic, and you can absolutely be empathic and remain neutral, there's a huge fallacy out there that says to be neutral, you must be dispassionate.

On the contrary..

IE: That's another Western cultural imposition because there's this almost like approach to always speak with this calm and, you know, this type of voice and anything above that is, if I may use your terminology, emotional dysregulation. It's not.

RLD: Well, again, everything's contextual. And you take your parties as you find them, and you have to take yourself as you find yourself. The difference is you get to work on yourself. When you're working with your parties, you have to build a process around them. If my parties are loud and that is their way of being, and they're telling me they're not upset, they're just being passionate. And this is how they talk at the dinner table. I'm not going to take that as a sign of concern so long as I don't have other evidence that it's not concerning. If the grandparents and the aunties and uncles play incredibly important roles in the children's lives, I'm not going to suggest that just because that isn't the model nuclear family that their roles as stakeholders in the conflict is not going to have impact. Of course it is, because they're key figures in the family and key figures in the children's lives. I think the thing is, is always taking our parties as they are learning who they are, being curious with who they are. And the thing about empathy, it doesn't require taking sides.

IE: But it is just seeing it.

RLD: It requires, yes, taking a person's perspective and putting language to that perspective. I don't ever need to say to someone, I agree what that other person did was bad. I don't even need to say: “oh, I agree that what that person did was hurtful”. I can just say that experience sounds hurtful. I'm sorry you felt that way. I'm allowed to have feelings of compassion for my parties. And more importantly, if we go back to trauma models, when people feel felt with, they feel safer. And when they feel safer, they go into their window of tolerance. And when they're in their window of tolerance, they can negotiate.

And that one thing I just want to make sure I cover because I know we covered hyper dysregulation and a tactic I shared with you, the tactic of “name it to tame it”. So some things I learned about hypo dysregulation, I'll just share one tip: which is anything that brings parties back into their bodies. So my trick here is, if in doubt, copy the paramedics. What do they do? They give you heat, they give you blanket, they give you hydration. So one of my favorite tricks is hot decaf drinks. I'll still have caffeinated drinks there because it's not good business practice not to. But when people are nearing the lower edge of their window of tolerance, by just introducing some heat and hydration, we can help them get back into their bodies. I spoke to a mental health practitioner who talked about crunchy foods. So there are all of these different hacks stuff in the real world and you know, in different cultural groups around the world, conflict is resolved and food is absolutely fundamental to that process. Sometimes it happens around a dinner table. Sometimes everybody meets for a meal and then they have a more formal conversation. We've evolved this way.

IE: So we're talking about conflict and trauma, but we are also seeing many long tracted conflicts. And I'm not only talking about business to business, person to person, but also community, countries. How does actually trauma affect people's capacity if it lasted that long and if it contributed from one trauma to another to another to another, where do we start? What can be done to start even?

RLD: So, I was just at the Transforming Trauma Conference in Oxford and I attended a wonderful session called “When there's no post” in reference to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. My first thought on this is: name it. Name that it's ongoing. Don't try and hide away from it. Let's not try and pretend people are in a place of safety if they're not. When we can look at it and say this is ongoing and it's painful and it feels like it's not going to end, then that's the beginning conversation. Over time, we can talk about what strategies need to be put in place to make things feel safer. Let's not pretend there's a post if there isn't. Let's deal with what we have in front of us.

In prolonged conflicts, a crucial ingredient is not trying to solve it fast. It's been going on for a very long time. Little tiny steps build micro trusts when they go well and they create micro tears or micro ruptures when they don't. But at least those are micro ruptures. I mean, I often think about this thing like clockwork. There's tiny little pieces of hurt, tiny little pieces of pain that create a big movement. But there's also tiny little mechanics of paperwork and law and different actors and different relationships and it's actually, quite complex. So, you know, I work in family law predominantly. Those conflicts, even if it's a very good relationship, once there's children, these people are in each other's lives for the rest of their lives potentially. And so a perfectly agreeable outcome could have arisen when the child was six, but now the child is nine and we have to revisit things and we have to look at what worked and what didn't and how the child has changed. And now the child is 15 and now the child is 18 and has gone off to university. And then somewhere after post secondary education, there's no longer financial obligations, but now the child is 28 and getting married. And so there's these consistent ongoing relationships with these consistent ongoing issues. And some of those issues will find resolution or there will be tactics. And sometimes, tactics don't work after a certain period of time because people change, situations change, contexts change. And so when change occurs, just a really healthy outlook is in the event of a change, we'll just go back to mediate. We'll talk about it, will explore the changes and see what needs adjustment and see what worked and has always worked and work through the impact on us as well of we worked so hard to get this structure and now it's not working anymore. And so I think part of it is looking at a prolonged conflict and saying: “This is hard. It doesn't come from nowhere. It's layers and layers and layers and layers. Let's treat it like a jawbreaker”.

IE: One thing at a time, yeah.

RLD: It's going to take some time to unravel. We're not always going to get it right. We're going to have to do all these micro experiments to figure out what does go right. But what I love about the idea of an experiment is that you use a hypothesis and sometimes it goes wrong. Doesn't mean anything's wrong, it just means that you have new information. Whereas I think people want certainty and predictability, especially in conflict.

IE: And also they don't want to invest the time and they want quick resolutions. And there is no such thing.

RLD: Well, I mean. I mean, there can be in certain conflicts, right? But the more dysregulated you are, the more certainty and predictability fast feels like what you're after. And so sometimes, it's about the reframe and just saying you might get micro certainty and micro predictability. But let's talk about what this isn't, as well. Let's get to know what this process is and I think that's helpful with protracted conflicts.

IE: We're a little bit back in the beginning. Why do we need to study neuroscience for you or for me you know, public health? Why do we need these side branches for mediators? Should legal education also involve some aspects of this, like trauma or some neuroscience for lawyers? What do you think of that?

RLD: That's part of the way that I conduct my education practice. For me, I think trauma, informed conflict resolution, so that's for lawyers as well as for mediators, is a core competency. I do not see it as a “nice to have” because you're dealing with people's behaviors and even as a lawyer, you're examining a conflict event in hindsight and then you're applying theories of the case to it. We want context, we want to understand what happens. It can only make your case better if you understand what the situation is.

IE: Maybe you develop it over the course of your practice, but there is no recognized need for such in legal education or in...

RLD: I will disagree with you there. So if you look at www.traumainformedlaw.co.uk, Rebecca Norris and Camilla Wells are doing an excellent job of bringing trauma informed practice to to England and Wales and to the UK. Iain Smith out in Scotland has done excellent work in trauma informed law. Aonghus McCarthy out in Ireland is an excellent trauma informed lawyer. Myrna McCallum out of Canada runs the Trauma Informed Lawyer podcast and she co-authored, along with Helgi Maki and others, a book on trauma informed law. So there's a movement out there. In fact, there's even a conference in Vancouver every year since 2024, called “Justice is Trauma” and Myrna McCallum runs that and a number of people from all over the world working in trauma informed law, trauma informed dispute resolution, trauma informed education, trauma informed healthcare… We come together and we trade notes and we learn from each other. So I think there is an increasingly recognized need and maybe it hasn't hit the tipping point yet, but I think it's well on its way there.

IE: Okay, that's great to hear because I took a course on trauma informed restorative justice and that was quite important, but I don't think it has become mainstream yet. This is great. I do think justice is trauma, often for victims especially. Is there anything else you would like to add?

RLD: To the extent that we're going to play with the phrase justice is trauma, I think justice can be trauma. I think the legal system can be traumatic for victims, for sure. Also for defendants, also for actors within the court, also for witnesses. I actually think that some of the legal system in and of itself is a response to trauma. Some of the laws that we have are. If you think about some of the campaigns we have for laws, the stories underlying those are deeply traumatic. The loss of loved ones, the deaths of children, the loss of spouses. These are deeply traumatic, grief based stories that lead to laws that shape the way that things are. I have so many thoughts about how the legal system evolved. So what I would say is this: It's important to recognize that when harm is done, it doesn't come from nowhere. It's not happening in a vacuum. It's important to look at who caused the harm and what happened there. What traumas might they have faced? What challenges might they have faced? When you look at a person who's been victimized, how was the victimizing event for them? And also what other events, what other traumas in their life exacerbated that event? Or what protective factors in their life helped mitigate the effects of the event for witnesses? What is it like for them? How is the court process traumatizing or not? I don't practice restorative justice per se. I have my level one certificate in restorative justice. I practice mediation for the most part. The two have loads in common and in restorative justice, people can bring in other people, other stakeholders, support people. What does it look like for the support person in a restorative justice case? So there's a famous case of Marlee Liss's restorative justice process and in that process, she talks about who her support person was and something that as a trauma informed practitioner, I think is if I were going to host that process, it wouldn't just be about staying trauma informed for Marlee and the person who caused Marlee harm, but also for all the participants in the process. And it's thoughtful and we do need some of us to be studying the neurosciences so that we can make sure that we're doing things in line with our neurobiological realities.

IE: Thank you very much Rahina. I really appreciate your time.

RLD: Thank you. Thank you so much for having me.

IE: In this episode, my guest was Raheena Lalani Dahya. She's a family law and community mediator in Toronto, Canada. She's teaching ADR at Humber Polytechnic and she's a faculty member of family law mediation programs in various institutions in Canada. She's a lawyer in Ontario and an unregistered barrister in England and Wales. She served in many leadership roles over the mediation field and is currently studying in a part time Master of Science in Applied Neuroscience program at King's College London as part of her ongoing research in ADR and neuroscience. Her more detailed bio will be in the website of We Can Find a Way.

So that's it for now. A special thanks goes to Ilan Bass for putting me in touch with Raheena. She is a lifetime learner. Like me, Ilan is also a typical ADR person who shares his knowledge and friends and connections for the ADR community overall. Greetings go to him to Japan where he is right now and please contact me if you want me to address a subject in the field that I have not yet covered here or know a conflict resolution specialist who does something that may be of interest for conflict resolution practitioners.

As always, I would like to conclude by saying that you please follow this podcast and its website, www.wecanfindaway.com. The website contains a transcription of the episode as well. Please like and share and repost the episode or excerpts that I share in the Instagram account of We Can Find A Way. I share them in LinkedIn, BlueSky. We Can Find A Way is also in many podcast platforms including YouTube, Apple and Spotify. As always, I like to close by thanking musician Imre Hadi and artist Zeren Göktan, who allowed me to use their music and photograph in the podcast. Thank you and hope to meet you in the next episode in November.

She's a family law and community mediator in Toronto, Canada. She's teaching ADR at Humber Polytechnic and she's a faculty member of family law mediation programs in various institutions in Canada. She's a lawyer in Ontario and an unregistered barrister in England and Wales. She served in many leadership roles over the mediation field and is currently studying in a part time Master of Science in Applied Neuroscience program at King's College London as part of her ongoing research in ADR and neuroscience.